AI Demolishes the Claim that Jesus Never Existed

AI Discovers the Historical Jesus

One of the most stunning claims around the internet insists Jesus never existed. Proponents claim that Jesus did not exist as a historical person, but rather exists as a mythological construct created long after He is said to have lived.

It seems like a strange claim. Could a person with over 2 billion followers never have existed?

Still, the answer lies with the evidence.

What does the historical evidence say?

Is there evidence that Jesus existed, or not?

How would this evidence compare to similar people from the time period?

To find out, I asked AI. After instructing it to forget everything I had previously entered and start fresh, I wrote this prompt:

Analyze the historical evidence for Jesus. Compare this evidence to the evidence we have for other notable figures around this time period.

This is how Grok answered:

AI’s Answer

Analyzing the historical evidence for Jesus of Nazareth involves examining primary and secondary sources from the 1st and 2nd centuries CE, both Christian and non-Christian, to assess his existence, life, and impact. To provide context, I’ll compare this evidence to that for other notable figures from roughly the same period (c. 50 BCE–100 CE), such as Julius Caesar, Cleopatra, Pontius Pilate, and Rabbi Hillel. The comparison will focus on the type, quantity, and quality of sources, their proximity to the figures’ lives, and their reliability, while addressing the unique challenges of studying Jesus as a religious figure. The analysis is grounded in historical methods and current scholarship as of April 16, 2025.

Historical Evidence for Jesus

Christian Sources

1. New Testament Gospels (Mark, Matthew, Luke, John):

Date: Written c. 65–100 CE (Mark ~65–70, Matthew and Luke ~80–90, John ~90–100).

Content: These are theological biographies detailing Jesus’ life, teachings, miracles, crucifixion (c. 30–33 CE), and resurrection. They draw on earlier oral traditions and possibly written sources (e.g., Q, a hypothetical sayings collection).

Strengths:

Written within 30–70 years of Jesus’ death, relatively close for ancient figures.

Multiple independent traditions (Mark, Q, John’s unique material) corroborate core details: Jesus as a Jewish preacher, teacher of parables, crucified under Pilate.

Reflect a vibrant early Christian movement, suggesting a significant historical figure.

Weaknesses:

Theological bias: Written by believers to promote faith, not neutral history.

Example: Mark 15:15: “So Pilate, wishing to satisfy the crowd, released Barabbas for them; and after flogging Jesus, he handed him over to be crucified.” This ties Jesus to a specific Roman governor, consistent across Gospels.

2. Pauline Epistles:

Date: Written c. 50–62 CE (e.g., 1 Corinthians, Romans).

Content: Paul, a former Pharisee converted c. 33–36 CE, mentions Jesus’ teachings (e.g., 1 Corinthians 7:10 on divorce), death, and resurrection (1 Corinthians 15:3–8). He met Jesus’ brother James and disciple Peter (Galatians 1:18–19).

Strengths:

Earliest written sources, within 20–30 years of Jesus’ death.

Paul’s encounter with James confirms Jesus’ family, a mundane detail unlikely to be invented.

Non-narrative focus reduces embellishment compared to Gospels.

Weaknesses:

Sparse biographical details; Paul emphasizes theology over history.

Written by a believer, not a neutral observer.

Example: 1 Corinthians 15:3–5: “For I handed on to you as of first importance what I in turn had received: that Christ died for our sins in accordance with the scriptures, and that he was buried, and that he was raised on the third day.”

3. Other New Testament Writings:

Date: c. 70–100 CE (e.g., Acts, Hebrews).

Content: Acts describes early Christian communities and mentions Jesus’ life indirectly. Hebrews references Jesus as a high priest figure.

Strengths: Corroborate the rapid spread of Jesus’ movement, implying a historical catalyst.

Weaknesses: Secondary to Gospels and Paul, with similar theological bias.

Non-Christian Sources

1. Josephus (Jewish Historian, 37–100 CE):

Source: Antiquities of the Jews (c. 93 CE).

Content: Two passages mention Jesus:

Testimonium Flavianum (Ant. 18.3.3): Describes Jesus as a wise man, teacher, crucified under Pilate, and founder of a persistent movement. Text reads: “About this time there lived Jesus, a wise man, if indeed one ought to call him a man… Pilate condemned him to be crucified… His followers did not abandon his discipleship.”

Strengths: Written ~60 years after Jesus’ death by a non-Christian Jew, providing external corroboration.

Weaknesses: Partially corrupted by later Christian scribes (e.g., “if indeed one ought to call him a man” likely added). Scholars (e.g., John Meier) reconstruct a neutral core, confirming Jesus’ existence, teachings, and crucifixion.

Josephus’ James Passage (Antiquities 20.9.1) mentions “James, the brother of Jesus, who was called Christ,” executed c. 62 CE.

Strengths: Widely accepted as authentic, confirming Jesus’ family and title.

Weaknesses: Brief, lacks detail.

Assessment: Josephus provides credible, near-contemporary evidence for Jesus’ existence and key events.

2. Tacitus (Roman Historian, 56–120 CE):

Source: Annals (c. 116 CE).

Content: Describes Nero blaming Christians for the Great Fire (64 CE): “Christus, from whom the name had its origin, suffered the extreme penalty during the reign of Tiberius at the hands of one of our procurators, Pontius Pilatus” (Annals 15.44).

Strengths: Non-Christian, hostile source confirms Jesus’ execution under Pilate, aligning with Gospels.

Weaknesses: Written ~80 years later, possibly drawing on Christian reports or Roman records.

Assessment: Strong corroboration of Jesus’ crucifixion and early Christian presence.

3. Suetonius (Roman Historian, 69–122 CE):

Source: Lives of the Twelve Caesars (c. 121 CE).

Content: Mentions “Chrestus” causing Jewish riots in Rome (c. 49 CE): “Since the Jews constantly made disturbances at the instigation of Chrestus, [Claudius] expelled them from Rome” (Claudius 25.4).

Strengths: May refer to Jesus (Chrestus likely a misspelling), showing early Christian impact.

Weaknesses: Ambiguous; “Chrestus” could be another figure, and it’s late (~80 years post-crucifixion).

Assessment: Weak but supplementary evidence of Christian activity linked to Jesus.

4. Pliny the Younger (Roman Governor, 61–113 CE):

Source: Letters (c. 112 CE).

Content: Describes Christians worshiping Christ “as if to a god” (Letters 10.96).

Strengths: Confirms early Christian devotion to Jesus, implying a historical figure.

Weaknesses: Late and focused on Christians, not Jesus directly.

Assessment: Indirect, supporting Christian spread.

Other Considerations

Absence of Evidence: No contemporary non-Christian records (e.g., Roman archives) mention Jesus directly, but this is unsurprising for a provincial preacher in a volatile region like Judea.

Mythicism: A fringe view denies Jesus’ existence, arguing he’s a mythic construct. This is rejected by most scholars (e.g., Bart Ehrman, Did Jesus Exist?, 2012) due to multiple attestations within decades of his life, unusual for minor figures.

Summary for Jesus:

Quantity: Moderate (Gospels, Paul, Josephus, Tacitus, etc.).

Quality: Mixed — early Christian sources are close but biased; non-Christian sources are later but independent.

Proximity: 20–80 years post-death, excellent for antiquity.

Key Corroborations: Existence, Jewish preacher, crucified under Pilate, brother James, early Christian movement.

Challenges: Theological bias in primary sources, limited non-Christian references.

Evidence for Comparable Figures (c. 50 BCE–100 CE)

1. Julius Caesar (100–44 BCE)

Sources:

Contemporary: Caesar’s own Commentarii de Bello Gallico (c. 50–40 BCE), Cicero’s letters (e.g., Ad Atticum, c. 50 BCE), and inscriptions (e.g., Fasti Capitolini).

Near-Contemporary: Suetonius (Lives, c. 121 CE), Plutarch (Parallel Lives, c. 100 CE), Appian (Civil Wars, c. 150 CE).

Content: Detailed accounts of Caesar’s campaigns, political career, assassination (44 BCE), and deification. Coins, statues, and Senate records corroborate events.

Strengths:

Abundant, diverse sources: self-authored works, rival accounts (Cicero), material evidence.

Written during or soon after his life, minimizing legend.

Non-biased sources (e.g., Cicero’s critiques) balance hagiography.

Weaknesses: Some later accounts (Suetonius) include gossip; deification myths exaggerate.

Proximity: 0–150 years, exceptional for antiquity.

Assessment: Gold standard for ancient figures due to volume, contemporaneity, and material corroboration.

2. Cleopatra VII (69–30 BCE)

Sources:

Contemporary: Coins, inscriptions (e.g., Egyptian stelae), Cicero’s letters (e.g., Ad Atticum 14.8, c. 44 BCE).

Near-Contemporary: Plutarch (Life of Antony, c. 100 CE), Cassius Dio (Roman History, c. 200 CE), Strabo (Geography, c. 20 CE).

Content: Chronicles her reign, alliances (Caesar, Antony), and suicide. Egyptian and Roman records confirm her rule and diplomacy.

Strengths:

Material evidence (coins, busts) and contemporary mentions (Cicero) confirm existence and role.

Multiple perspectives (Roman, Egyptian) reduce bias.

Weaknesses:

Later sources (Plutarch) romanticize or vilify her, introducing bias.

Few Egyptian primary documents survive due to papyrus decay.

Proximity: 0–170 years, very strong.

Assessment: Robust evidence, though less voluminous than Caesar’s, bolstered by material and cross-cultural records.

3. Pontius Pilate (Governor, c. 26–36 CE)

Sources:

Contemporary: The Pilate Stone (archaeological find, 1961), an inscription naming “Pontius Pilatus, Prefect of Judea.”

Near-Contemporary: Josephus (Antiquities 18.3.1, c. 93 CE), Philo (Embassy to Gaius, c. 40 CE), Tacitus (Annals 15.44, c. 116 CE), Gospels (c. 65–100 CE).

Content: Describe Pilate’s governorship, clashes with Jews, and role in Jesus’ crucifixion.

Strengths:

Archaeological confirmation (Pilate Stone) ties him to Judea.

Multiple sources (Jewish, Christian, Roman) corroborate his tenure and character.

Weaknesses:

Limited detail beyond governorship; Christian sources focus on Jesus’ trial, possibly exaggerating.

Proximity: 10–80 years, excellent.

Assessment: Strong evidence for a minor official, enhanced by archaeology and diverse attestations.

4. Rabbi Hillel (c. 50 BCE–10 CE)

Sources:

Near-Contemporary: Mishnah (c. 200 CE, oral traditions from 1st century), Talmud (c. 500 CE), Josephus (Antiquities 15.3.1, c. 93 CE, indirectly on Pharisees).

Content: Hillel’s teachings (e.g., Golden Rule, Mishnah Avot 1:12), role as a Pharisaic leader, and legal innovations (e.g., prosbul debt rule).

Strengths:

Early oral traditions, codified later, reflect a historical figure influential in Judaism.

Josephus confirms Pharisaic prominence, supporting Hillel’s context.

Weaknesses:

No contemporary texts; Mishnah is 150–200 years later, risking legend.

Biographical details are sparse, focusing on sayings.

Proximity: ~100–150 years, weaker than Jesus or political figures.

Assessment: Moderate evidence, reliant on later Jewish tradition, less robust than Jesus due to delayed codification.

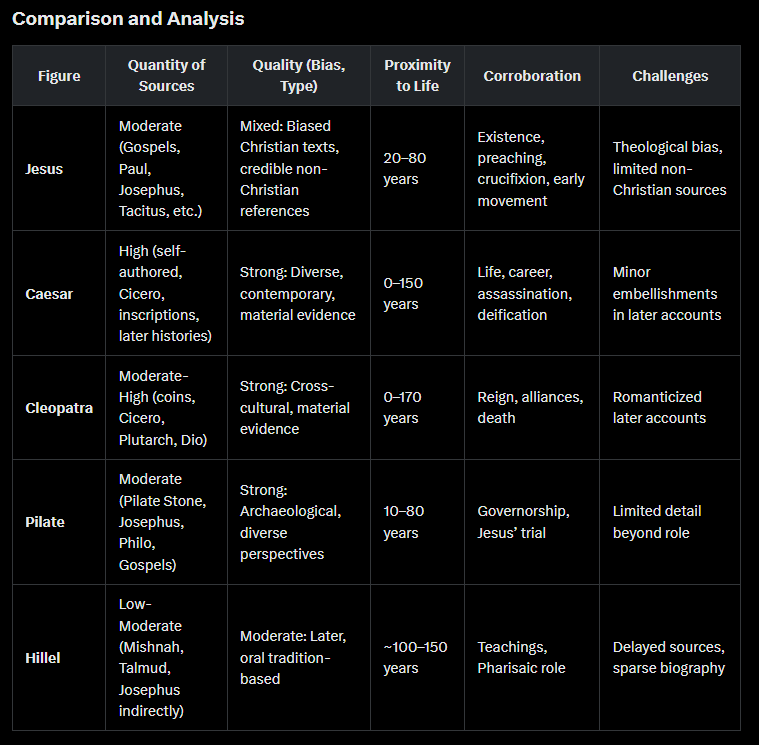

Key Observations:

Quantity:

Caesar has the most sources, reflecting his political prominence. Cleopatra and Pilate follow, with Jesus comparable to Pilate but exceeding Hillel.

Jesus’ evidence is notable for a non-elite figure, surpassing many contemporaries outside ruling classes.

2. Quality:

Caesar and Cleopatra benefit from contemporary, non-biased sources (Cicero, inscriptions). Pilate’s archaeological find and diverse accounts enhance reliability.

Jesus’ Christian sources are biased but early and numerous, with non-Christian corroboration (Josephus, Tacitus) adding credibility. Hillel’s reliance on later oral tradition weakens his case.

3. Proximity:

Jesus’ sources (Paul at 20 years, Gospels at 30–70 years) are closer than Hillel’s (100+ years) and competitive with Pilate’s (10–80 years). Caesar and Cleopatra have contemporary records, an advantage due to their status.

Jesus’ proximity is strong for a religious figure in a peripheral region.

4. Corroboration:

Jesus’ core details (existence, preaching, crucifixion) are multiply attested, like Caesar’s career or Cleopatra’s reign. Pilate’s role is similarly corroborated. Hillel’s teachings are less concretely verified.

Non-Christian sources for Jesus, though brief, align with Christian claims on key points, unlike mythical figures (e.g., Hercules) with no external attestation.

5. Challenges:

Jesus’ evidence faces theological bias, but this is mitigated by early dating and external references. Caesar and Cleopatra face minor embellishment, while Hillel’s delayed sources risk legend. Pilate’s evidence is narrow but reliable.

Unique Aspects of Jesus’ Case:

As a religious figure, Jesus’ sources are primarily from followers, unlike political figures with state records. Yet, non-Christian mentions (Josephus, Tacitus) are rare for such figures, strengthening his historicity.

The rapid spread of Christianity (e.g., Paul’s churches by 50 CE) implies a historical catalyst, unlike slower myth development.

Compared to Hillel, Jesus has earlier written records, despite similar cultural constraints (oral tradition, religious context).

Conclusion

The historical evidence for Jesus is robust for a 1st-century religious figure, comprising early Christian texts (Paul, Gospels) within 20–70 years and non-Christian references (Josephus, Tacitus) within 60–80 years. Core details — existence, Jewish preaching, crucifixion under Pilate, and early movement — are well-corroborated, with challenges from theological bias mitigated by external sources. Compared to contemporaries:

Caesar and Cleopatra have superior evidence due to contemporary records and material artifacts, reflecting their elite status.

Pontius Pilate matches Jesus in proximity and corroboration, bolstered by archaeology, but has narrower scope.

Hillel has weaker evidence, with later, less diverse sources, making Jesus’ record stronger despite similar religious context.

Virtually all historians (e.g., Ehrman, Sanders) affirm Jesus’ existence and key events, placing him on par with minor historical figures like Pilate and ahead of figures like Hillel in evidentiary terms. While not as documented as elite figures, Jesus’ evidence is compelling for his time and status, firmly establishing him as a historical figure.

If a real miracle working Jesus did live, then so do talking serpents and donkeys. The AI are showing how stupid they/we can be and are. AI should believe the Bible when it says that God is unknowable, unfathomable and works in mystery. I like A I. It makes a good adding machine. Too stupid for words though.